In this commentary, I discuss the implications of new work from Hanneke Den Ouden's lab. The authors subdivided Parkinson's disease patients into those with and without tremor, and found that learning was affected by dopamine in opposite directions in the two groups!

Manohar Brain 2020 [commentary]

Sometimes we plan ahead, thinking about future consequences of our actions. Other times, we select actions based only on their immediate reward associations. Planning ahead is crucial to staying healthy, but might be affected by motivation.

We asked whether hunger affects planned vs directly reinforced action

van Swieten, Bogacz & Manohar Cogn. Aff. Beh. Neurosci. 2021We found that people learned quicker about action values when they were hungry. Hunger didn't affect planning.

Overall, hunger may actually improve our decision-making.

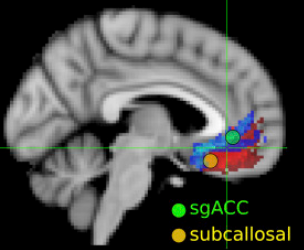

Learning from reinforcement is a classic way to study how brain areas contribute to adaptive behaviour. The most frontal parts of the brain probably contribute at a very high, abstract level. In this study , we asked how confident people are in what they have learned.

Manohar et al. Cortex 2021Healthy people are biased by previous choices, and by competing information, when making these "meta-cognitive" estimates. However, patients with selective damage to the medial prefrontal cortex lacked these biases. They were effectively better at this. One patient had lesions on both the left and the right side, and he outperformed all the 47 other people in the study!

Patients with Parkinson's disease lack the brain chemical dopamine. Dopamine is thought to signal upcoming rewards, and this might explain why patients on treatment can develop impulse control disorders.

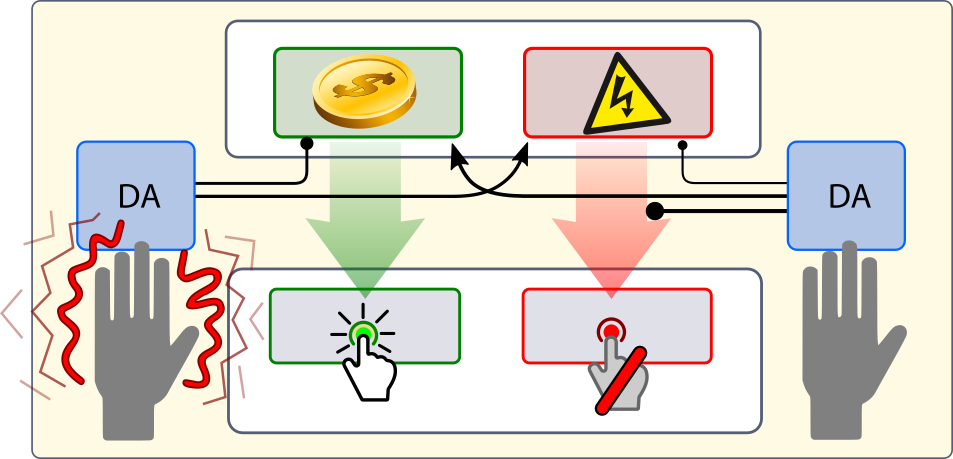

My lab is studying two different ways to motivate people. One way is to reward or punish them based on how well they do -- like performance-related pay. The other way is to promise a guaranteed reward, which also tends to keep people motivated (even though they don't have to). Both these kinds of motivation have been linked to dopamine in different ways.

In our study, we found that dopamine boosted performance-related motivation. This may be because it helps patients act 'instrumentally', amplifying the contingency between their actions and the rewards. And surprisingly, dopamine also reduced the effect of guaranteed rewards.

The results suggest that giving dopamine in Parkinson's doesn't directly increase reward sensitivity, but rather, increases the coupling between incentives and actions.

Grogan et al. eLife

2021

Grogan et al. eLife

2021

Learning from reinforcement is a classic way to study how brain areas contribute to adaptive behaviour. The most frontal parts of the brain probably contribute at a very high, abstract level. In this study ( Manohar et al. Cortex 2021), we asked how confident people are in what they have learned.

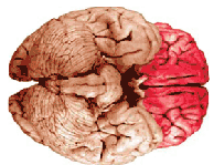

Underside of a human brain

Healthy people are biased by previous choices, and by competing information, when making these "meta-cognitive" estimates. However, patients with selective damage to the medial prefrontal cortex lacked these biases. They were effectively better at this.

One patient had lesions on both the left and the right side, and he outperformed all the 47 other people in the study!

Manohar et al. Cortex 2021

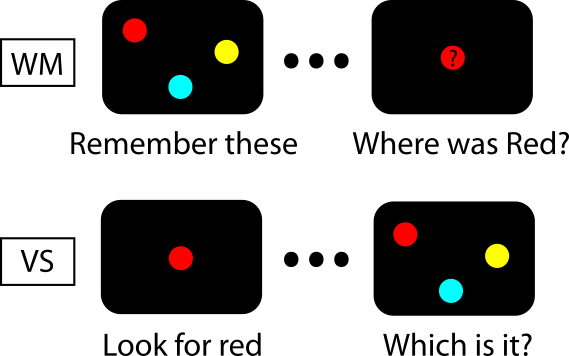

When you recall an item from memory, a prompt usually brings associated parts of that item into mind. Could this process be the same thing that occurs when you search for a visual target?

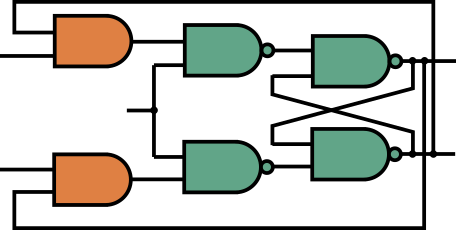

We tested a neural model designed to perform working memory tasks, to see if it could also perform visual search.

The model retrieves information when a partial cue re-activates a pattern of neurons by associative pattern completion. This same process could occur when we look for an item that we have in mind: the target in mind corresponds to information in memory, and the display that must be searched corresponds to a (complicated) retrieval cue.

We found that when pattern completion is applied to the search display, the memory item "amplifies" matching features in the display. Remarkably, this reproduces a number of classical findings in the visual search literature.

Importantly, the model also gets some things wrong. This shows us that there are certain mechanistic differences between memory and search.

"A common neural network architecture for visual search and working memory", Bocincova et al., Visual cognition (2020)

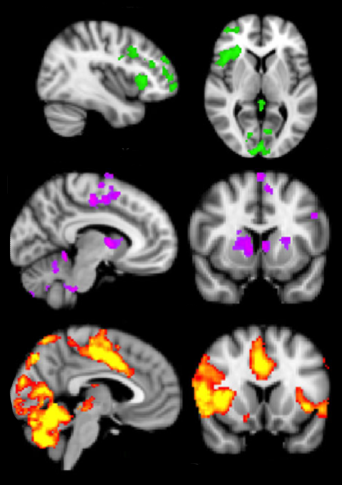

Damage to specific brian areas increase or decrease responses to incentives.

"Human ventromedial prefrontal lesions alter incentivisation by reward", Manohar & Husain Cortex 2016

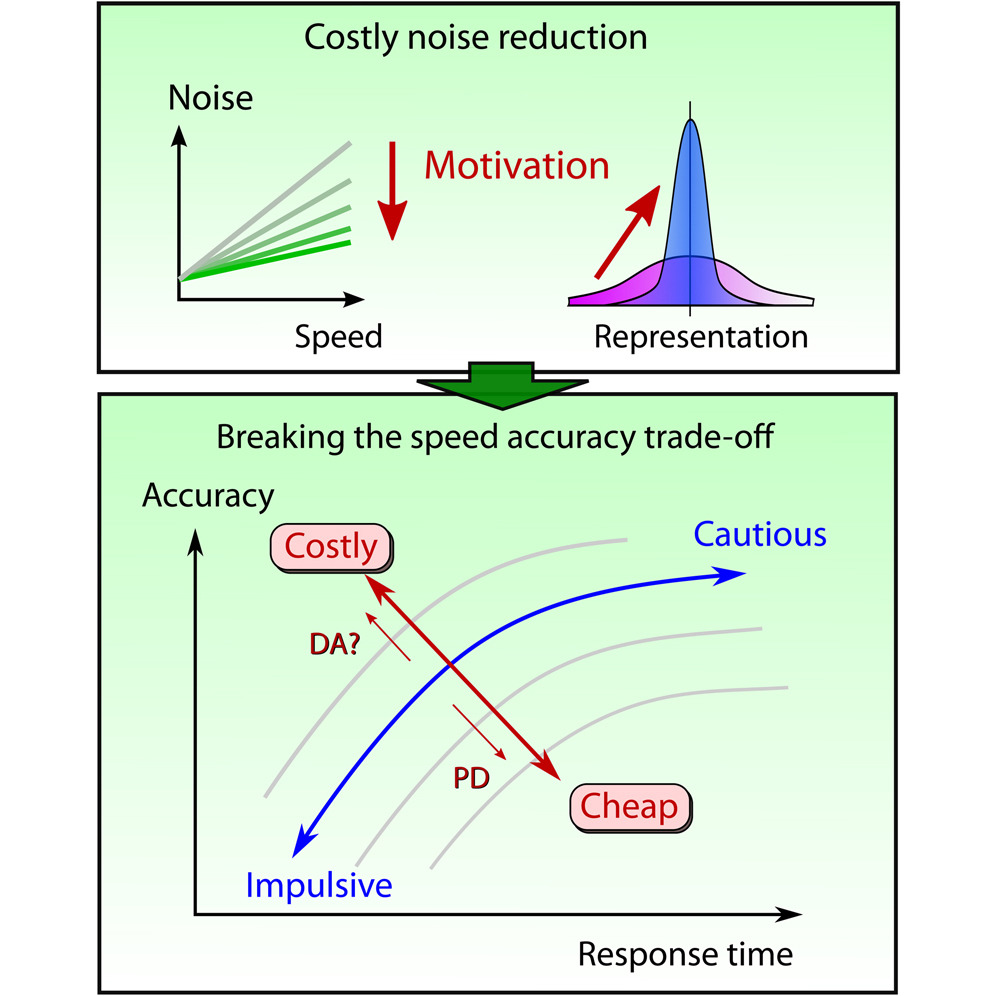

In this study we show that rewards and dopamine improve motor performance by reducing internal noise. Reward violated the speed-accuracy trade-off in motor control, and also in cognitive control. In both cases, the benefit can be explained in terms of reducing the effects of internal noise.

In patients with Parkinson's disease, the cost of reducing noise was greater, suggesting that dopamine may be crucial in paying the cost.

"Reward pays the cost of motor and cognitive control", Manohar et al. Current Biology 2015

Motivation increases the strength of error-corrective internal feedback, making movements more robust to variability:

"Motivation dynamically increases noise resistance by internal feedback during movement" Manohar et al., Neuropsychologia 2019

People are motivated to put in more effort for both by performance-dependent pay, and by fixed guaranteed pay. But these two traits are uncorrelated across people! Which type of person are you?

"Distinct motivational effects of contingent and noncontingent reward" Manohar et al. Psychological Science 2017

In patients with Parkinson's disease, when off medication, motivation by reward contingencies is reduced. This is restored by medication, but motivation by guaranteed rewards is reduced. Therefore, the two types of motivation are affected oppositely by the neurotransmitter dopamine.

"Dopamine promotes instrumental motivation, but reduces reward-related vigour" Grogan et al., eLife 2020

Recently we have developed a neural model of working memory, proposing a very simple network. It is unlike previously proposed mechanisms, because it suggests that the patterns of brain activity do not correspond to what we are remembering. Rather, rapid interference leads to highly variable -- but predictable -- codes in prefrontal cortex. "Neural mechanisms of attending to items in working memory", Manohar et al., Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (2019 )

Damage to some brain areas causes abnormal, misdirected motivation -- sometimes leading to compulsive stereotyped behaviours, or unplanned impulsive acts. This can sometimes be dramatic, causing considerable embarassment for patients and their families.

A loss of motivation results in clinical apathy -- a disabling disorder that can be difficult to pin down. It is often missed, and is hard to quantify. It carries a huge social and economic burden, and is often frustrating and distressing for carers.

We study what motivation is, in terms of computations. Is it the selection of an appropriate action, given a goal? Or is it the willingness to invest energy, at a cost, in a rewarding course of action? We found that:

Working memory is our ability to hold information in mind, for short periods of time. It can be disrupted by almost any brain problem. It has been difficult to pinpoint where and how such immediate memories are held.

We study short-term visual memories, measuring our memory capacity, how memories decay, and are disrupted by irrelevant information.